Uncategorized

A Trained, Prepared Staff… A Saved Life

By Gina Mayfield

In Calcasieu Parish, Louisiana, sits the Lake Charles plant of LyondellBasell, one of the largest plastics, chemicals and refining companies in the world. On one hot August morning, Safety Engineer Chris Chaisson went about his usual routine. “There was nothing really special what was going on that day. We were just making our rounds through all the security stuff, just checking things, seeing how people were doing and if there were any issues,” he says.

That’s when the call came in: “Man Down!” As Chris raced to the scene, he got word that EMS had already been dispatched, so he started delegating important tasks to those he encountered along his way: Go to the road and flag in the ambulance. Take the keys and open the guard gate. Guide the ambulance to come straight in and back up to the scene.

“As soon as I walked up to the patient, everyone backed away. It was a strange feeling like I had some kind of specialized training that they didn’t,” Chris says. “That was a little different than what I would have expected. I would’ve expected to help, not be expected to lead.”

As the crowd parted, Chris saw a CPR and AED-trained maintenance supervisor using an AED to analyze the heart rhythm of the patient, one of the site’s millwrights responsible for maintaining the plant. The AED provided instructions on how to proceed. About the same time that EMS arrived, so did Dawn Hinton, the on-site nurse practitioner, and Amanda Hebert, the security account manager for the site.

“EMS allowed the three of us to rotate as we continued to provide CPR,” Chris says. “They believed we were doing a good enough job, where they didn’t even take over.”

Eventually, the AED stopped recommending shocks. “We got a good rhythm on him, got him stabilized and into the ambulance,” Dawn says. At the hospital, it was no surprise when doctors determined the patient had gone into cardiac arrest. The next day they implanted stents to correct a left main artery almost 100 percent blocked. After a few days, the hospital released the patient to a very appreciative wife.

“The beautiful thing about this scenario is the amount of response we had,” Chris says. “We probably had a dozen people who were involved overall.”

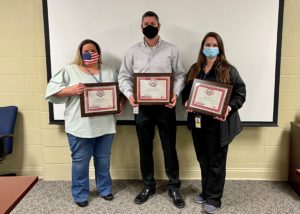

Left to right: Amanda Hebert, Chris Chaisson, and Dawn Hinton

He offers a valuable reminder. “These medical emergencies can happen anywhere, anytime. Having the ability to respond is everything, like in our situation, as soon as we walked up everyone drew back. They expected us to do something about it. So you might find yourself in a situation in which you’re viewed as the leader of the response. You want to be prepared.”

The plant offers CPR training on a regular basis for its electricians, supervisors and others who want lifesaving education. “The most important thing is having multiple trained, responders on site and an AED that’s readily available,” Chris says. Within less than three minutes, employees had the AED on the patient and were performing CPR.

“Those cycles of giving compressions and resting were so important to us because that allowed us to have the bench strength to recover. Providing quality CPR takes a lot of energy. The ability to have three to five people able to rotate in and out made all the difference,” Chris says. “We had all the help we could ask for. It was a picture perfect response.”

‘Father’ of CPR: Guy Knickerbocker, Who Helped Pioneer a Lifesaving Technique, Dies at 89

As a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University, Guy Knickerbocker, PhD, was one of three researchers who developed cardiopulmonary resuscitation, also known as CPR, which has saved countless lives.

Guy Knickerbocker, PhD

He died June 21, 2022 in Narvon, PA. He was 89.

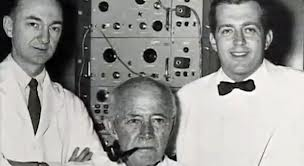

Knickerbocker was an electrical engineer and doctoral student at Johns Hopkins University where he collaborated with William Kouwenhoven, PhD, also an electrical engineer and professor, and James Jude, MD, a cardiac surgeon and resident at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, to develop the prototype of the first portable external defibrillator in 1957.

A year later, Knickerbocker made a crucial observation while working with Kouwenhoven and Jude. He discovered that pressure on the chest during defibrillation experiments in animals produced an arterial wave form and a temporary rise in blood pressure. This observation paved the way toward a new technique, which is now known as CPR.

The team published their research breakthrough on the value of external cardiac massage in providing blood flow to vital organs for people in cardiac arrest in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 1960.

“Anyone, anywhere, can now initiate cardiac resuscitative procedures,” the researchers noted in the landmark paper. “All that is needed are two hands.”

From left to right: Drs. James Jude, William Kouwenhoven and Guy Knickerbocker are regarded as the “Fathers of CPR.”

The brilliant trio would come to be regarded as “the fathers of CPR.”

In the early 1960s, Knickerbocker also collaborated with others to produce the training film titled, “Pulse of Life,” which was viewed by millions and popularized CPR.

Throughout his career, he published over 30 articles about electricity and the human body, according to his obituary.

William Montgomery, MD, FAHA, who serves as the coordinator for the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR), said Knickerbocker will always be remembered for his incredibly important work in the laboratory and in training activities.

Montgomery first met Knickerbocker at an AHA National Conference on CPR and Emergency Cardiovascular Care (ECC) in 1985 when Knickerbocker was among the first group of “Giants” in resuscitation science honored by the AHA for their landmark contributions to CPR and emergency cardiovascular care.

Left to right: Drs. James Jude, Guy Knickerbocker, Peter Safar and James Elam were among the first group of “Giants” in resuscitation science honored by AHA in 1985 at the organization’s National Conference on CPR and Emergency Cardiovascular Care (ECC).

Montgomery said in recent years, Knickerbocker and his wife, Joan, attended the Citizen CPR Foundation’s Emergency Cardiac Care Conference (ECCU), where he met with cardiac arrest survivors who were saved because of his breakthrough research.

“Those survivors were so happy to meet with him in person and individually and take pictures ‘with the man who invented the technique that saved their lives,’ Montgomery recalled. “These were very warm and emotional meetings and Guy was always very gracious with everyone.”

It was during the ECCU events where Dianne Atkins, MD, chair of the AHA ECC Committee, would meet with Knickerbocker.

“He was always a very pleasant man and willing to have his picture taken with everyone who asked,” Atkins remembered. “He seemed quite humble about his accomplishments with respect to CPR, but also was quietly proud of them.”

Atkins said it is now known that immediate CPR, usually delivered by a lay rescuer, is a primary determinant of survival with good functional outcome. Yet, she said less than 50% of patients in cardiac arrest in the U.S. receive CPR before EMS arrives.

Dianne Atkins meets with Guy Knickerbocker at the ECCU event in 2017.

“The AHA and the ECC need to commit to better understanding how to engage the lay public in understanding the need for CPR, improve the percentage of those who receive lay rescuer CPR and to ensure that our teaching methods are the most effective for providing high-quality CPR,” she said.

Knickerbocker and his research team fundamentally changed the way in which patients with cardiac arrest are treated, said Comilla Sasson, MD, vice president of ECC Science and Innovation at AHA. To continue his legacy, she said that the AHA is committed to teaching CPR to everyone.

“The American Heart Association is dedicated to making sure every person knows how to perform CPR, and can help save a life,” Sasson said. “And that all people, regardless of where they live or what healthcare system they are treated in, will have an equitable chance for surviving a cardiac arrest event.”

Another major way that Knickerbocker’s legacy can endure is for AHA and ILCOR to continue to support innovative research, said Robert Neumar, MD, who co-chairs ILCOR.

“We need to advocate for greater investment in resuscitation science and expand the pipeline of young scientists entering the field,” Neumar said.

Montgomery said Knickerbocker will always be remembered as being one of the original scientists and investigators that discovered modern CPR as we know it today.

“Even though he has passed, he will aways live in the hearts and minds of all providers of CPR and survivors as a ‘Giant’ in resuscitation and the person responsible for discovering the technique that ‘saved my life,’ Montgomery said.

Cardiac arrest survivor’s efforts to install AEDs in her community helps save a man’s life

Local cardiac arrest data informed Lynn Blake’s strategy to determine AED locations that contributed to a timely save

Last July, Doug Schwartz was enjoying dinner with his girlfriend, Shelly Belknap, and a friend at eTown restaurant located in Edwards, Colorado when he began to feel faint, and he suddenly suffered a cardiac arrest.

Shelly, who is an oncology nurse at Vail Health, was sitting next to Doug and immediately started CPR. Stephen McGaffick, an employee at eTown who is also a Beaver Creek Ski Patrol member, took turns with Shelly and performed CPR on Doug.

Fortunately, an automated external defibrillator (AED) was located about 100 yards away outside in a heated box attached to a lamppost in the Riverwalk, which is Edwards’ downtown area.

The AED that was used to help save Doug’s life was in this heated box attached to the lamppost.

A restaurant patron named Megan went to go grab the AED. When Megan returned with the AED, Shelly and Steve applied the device, which delivered two shocks by the time the paramedics arrived.

The paramedics took over and helped revive Doug. The restaurant patrons, who anxiously waited for an update on Doug’s condition, erupted into applause once they heard that he was alert.

Doug was transported by ambulance to Vail Health Hospital and then transported by helicopter ambulance to Denver that night. He spent five days in the ICU at Medical Center of Aurora and was then discharged.

Placing AEDs in key locations can make the difference between life and death. A person’s chance of survival decreases by 7 to 10 percent for every minute that passes without defibrillation.

The AED used to help save Doug’s life was one of more than 100 devices that had been strategically placed throughout Eagle County, Colorado about seven years ago thanks to the efforts of a local resident named Lynn Blake, a strong advocate for public AED implementation programs and quality improvement initiatives for cardiac arrest outcomes.

“I was flooded with emotions for a man I never met,” Lynn said when she learned that Doug’s life had been saved thanks to CPR and the use of the AED. “He was the reason I devoted so much of my life to implementing these programs, it was all for this man and his family.”

Lynn’s journey with advocating for the AED program in Eagle County traces back to her own personal story as a cardiac arrest survivor.

Surviving a Cardiac Arrest Spurs CPR and AED Advocacy Work

The start of 2007 was a whirlwind for Lynn. She got married on Feb. 3 and went on her honeymoon two days later. As soon as she returned from her trip, she began a new job in Vail, which is also located in Eagle County.

On Feb. 14, 2007, Lynn, 27, was on the second day of her job when she suddenly experienced cardiac arrest. One of Lynn’s co-workers, Sue Froeschle, whom Lynn hadn’t even met yet, immediately started CPR while another employee called 911 and ran to get help from the Vail Fire station that was across the street. Eagle County paramedics were also nearby; they quickly arrived and used a defibrillator to deliver three shocks to her heart.

(Left to right): Lynn Blake holds her baby, Thomas, with her rescuer and friend, Sue Froeschle

Lynn survived the incident and now has an implantable pacemaker defibrillator. She finally met Sue a year later when the American Heart Association gave an award to the first responders who helped save Lynn’s life. After the event, Lynn and Sue became very close. Her son is even named Thomas Froeschle Blake.

“There were so many coincidences and ironic details that allowed me to survive – I felt so compelled and convinced that my life was saved for a reason,” Lynn said.

Lynn didn’t know anything about cardiac arrest before the incident. She started researching to learn more about the condition. She also became an American Heart Association CPR instructor so that she could teach others how to save lives.

Throughout those early days of investigating, Lynn learned that cardiac arrest is a leading cause of death in the U.S. Yet, she was confounded that she couldn’t find any data on incidences and outcomes anywhere.

“No one could tell me who experiences cardiac arrest in Eagle County or even Colorado,” she recalled. “I could not find any information that was truly validated. Everything was an estimate.”

It wasn’t until she read a book titled, “Resuscitate,” that she learned about the Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES), a quality improvement program that works with EMS communities to collect data and measure out-of-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes.

After connecting with CARES and learning more about the program, she worked with local health authorities and volunteers to secure funding so that Eagle County could participate in the registry starting in 2014. She then worked with officials to get the state of Colorado to participate in CARES in 2019.

Lynn said it’s imperative to track how bystanders and EMS are responding to cardiac arrest to identify the necessary intervention strategies that will optimize the chain of survival.

“I can’t say ‘you need to learn CPR and have an AED’ if we don’t know if people are performing CPR and using AEDs,” she said. “It’s impossible to improve resuscitation outcomes if you don’t know what you’re improving. Data collection allows not only the community to figure out how citizens should be engaged, but also gives agencies a way to measure their performance. Quantitative analysis of cardiac arrest is the linchpin to successful resuscitation, and it must happen for the conversation to continue.”

Using Data to Guide AED Placement in Eagle County

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a global public health issue experienced by 3.8 million people annually. Only 8% to 12% survive to hospital discharge. Early defibrillation of shockable rhythms is associated with improved survival, but ensuring timely access to defibrillators has been a significant challenge.

Public-access defibrillation is the use of AEDs by the public to facilitate CPR and early defibrillation before professional responders arrive. A recent International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) scientific statement commissioned by the American Heart Association evaluated the barriers to public-access defibrillator use and early defibrillation. The statement titled, “Optimizing Outcomes After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest With Innovative Approaches to Public-Access Defibrillation,”also identified the opportunities for new approaches to public-access AED program implementation.

Public-access defibrillation has saved many lives. Unfortunately, public-access AEDs still remain underused. The devices are used in less than 3% of OHCAs.

However, people who experience OHCA with a nearby AED are three times more likely to receive bystander defibrillation and twice as likely to survive as those without an AED nearby, according to the statement. Unfortunately, AEDs are rarely close enough for timely retrieval. The issue is further compounded by the fact that even when a registered AED is near a cardiac arrest incident, most go unrecognized and unused. The ILCOR statement calls for using innovative approaches to improve public-access defibrillation in the future by optimizing AED availability, reliability and usability through coordinated, data-driven, regional strategies.

When Lynn worked with officials in various Eagle County communities to place the more than 100 AEDs, it was important to them that the devices were easily accessible and not placed behind locked doors like they had typically been in the past.

However, she said there was some initial reluctance among entities to place public defibrillators, especially outside and unsecured. She said the entities feared liability, theft, people using them unnecessarily, and freezing temperatures.

Through education efforts, Lynn helped the entities understand the crucial need for AEDs by sharing statistics and the fact that theft is fairly uncommon. She worked to ensure that the AEDs were placed outside in heated boxes attached to lamp posts where they’d be available 24/7.

Additionally, the ILCOR statement discusses the value of geographic cardiac arrest data to inform AED placements such as density maps of OHCAs that plot incidences on a map that can pinpoint higher-risk spots for cardiac arrest and prime locations for AEDs.

Using data from CARES, Lynn said AEDs were placed in the most common public locations for cardiac arrest emergencies such as healthcare/nursing home facilities, schools and libraries throughout the county. Then, the most highly-trafficked public places were identified using Eagle County’s geographic information system and Google maps. Lynn said it wasn’t realistic to place a unit in every small business, plus the lifesaving devices needed to be accessible 24/7.

“This started the outdoor cluster approach, installing heated cabinets to light posts in the most centrally accessible points to multiple establishments,” she said. “Deploying one unit for numerous places significantly diminishes the cost and increases accessibility. “

Lynn said she worked with her neighborhood of EagleVail to install defibrillators at major residential and golf/Nordic course intersections because CARES data suggests that residences are the most commonplace for cardiac arrests to occur.

“Hopefully, someday in the near future, defibrillators will be as common as microwaves in homes,” she said. “Until then, we must continually strive for the ubiquity of these lifesaving devices. There is so much more that can be done, but working from the grassroots up is very difficult. Federal mandates and more awareness must occur to achieve the availability needed.”

‘It Took a Village to Save Doug’

Left to right: Doug Schwartz and Lynn Blake at the coffee shop.

In December, Lynn and Doug met for the first time at a coffee shop.

“I was very grateful,” Doug said. “That is what I tried to communicate to Lynn in my meeting. It is strange to sit across the table from somebody who played a part in saving your life.”

He said he feels very fortunate with the way the events unfolded last July from receiving high-quality, immediate CPR from Shelly to Megan grabbing the AED nearby.

“I don’t know how you could draw up a plan any better with the timeliness of my save,” he said.

For Lynn, it was a dream come true to meet Doug whose life was saved with the help of an AED program that she and other volunteers developed after she received a second chance at life. It’s also a testament to the chain of survival that improved once the community started tracking and measuring data to make changes that save lives.

“It took a village to save Doug,” she said. “There are so many components that have to take place to save one life.”